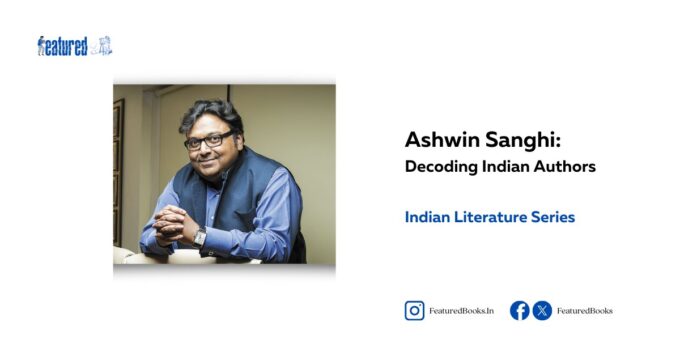

Ashwin Sanghi occupies a unique and distinguished place in contemporary Indian popular fiction, especially in the genre of mythological and historical thrillers. His literary works offer a rare synthesis of myth, history, science, and suspense, demonstrating a refined understanding of India’s ancient civilisations while speaking in a voice that resonates with the modern reader. Sanghi’s novels stand out not merely because of their subject matter but because of the depth of research, intellectual rigour, and thematic audacity he brings to them. In a literary landscape that has recently witnessed a surge in mythological fiction, with notable authors like Amish Tripathi and Anand Neelakantan offering rich reinterpretations of ancient Indian epics, Sanghi differentiates himself by employing a markedly different approach, both in terms of narrative structure and philosophical scope.

Sanghi’s works are meticulously researched and unapologetically cerebral. Each novel reads almost like a historical thesis camouflaged within a page-turning thriller. For instance, in Chanakya’s Chant, he explores the power dynamics of ancient and modern India through the dual narrative of Chanakya and his modern-day reincarnation. This intertwining of timelines, where the past and present converse across centuries, is one of Sanghi’s defining narrative techniques. The reader is compelled to notice not merely the historical parallels but the continuities in human ambition, power struggles, and ethical paradoxes. His ability to construct such metaphoric and structural symmetries across epochs is what sets him apart. Unlike Tripathi, who primarily delves into the philosophical and moral quandaries of divine and semi-divine figures, Sanghi focuses more on political intelligence, strategy, and sociological continuity, often avoiding overt spiritualisation in favour of realism laced with symbolism.

Moreover, Sanghi’s signature lies in his use of an investigative framework. His thrillers operate not only as mythological retellings but also as intellectual puzzles. In The Krishna Key, for example, Sanghi crafts a fast-paced thriller centred on the search for Krishna’s legacy in contemporary times. Drawing on Indic texts, archaeology, symbology, and even genetic science, Sanghi compels the reader to consider the plurality of knowledge systems in ancient India. His prose frequently references not just myth but also Vedic mathematics, astronomical treatises, and Tantric traditions, thereby underscoring the scientific depth of Indian civilisation. This mode of storytelling diverges significantly from that of Neelakantan, whose strength lies in subversive reinterpretations of characters. Neelakantan gives voice to marginalised or vilified characters like Ravana and Duryodhana, thereby humanising the supposed villains of epics and encouraging the reader to consider moral relativism. While Neelakantan’s work thrives on empathy and emotional nuance, Sanghi prefers an analytical and expository mode, wherein characters serve as conduits for larger historical and philosophical debates.

Another unique dimension of Sanghi’s work is his preoccupation with geopolitical and civilisational continuity. In novels like The Rozabal Line, he ventures into bold thematic terrain, such as the theory that Jesus Christ may have lived and died in India. Such an assertion, though highly speculative, is rendered with such scholarly scaffolding and narrative conviction that it challenges conventional understandings of religious history. Sanghi is not merely retelling mythology; he is reconfiguring global historical narratives through an Indic lens. His use of speculative historiography, intertwined with real-world conspiracy theories, bears a resemblance to the work of Dan Brown, whom Sanghi has publicly acknowledged as a significant influence. However, unlike Brown, Sanghi is deeply embedded in India’s cultural, ritualistic, and historical psyche, giving his work a rooted authenticity.

His language further enhances this rootedness. Sanghi’s prose is deliberate, restrained, and scholarly without being inaccessible. His writing often reflects his background in business and history, allowing him to imbue his stories with the precision of a strategist and the perspective of a cultural historian. By contrast, Amish Tripathi employs a more emotional and evocative register. Tripathi’s Shiva Trilogy, for instance, is less concerned with historical accuracy and more invested in spiritual symbolism. His characters are carriers of metaphysical truths, and the narrative is structured like a modern-day parable. Tripathi’s Lord Shiva is a Tibetan tribal warrior who ascends to divine status, embodying the idea that greatness lies in karma rather than birth. While this offers a refreshing democratic re-imagination of divinity, it is ultimately mythopoeic rather than historiographic.

In contrast, Sanghi resists such overtly spiritual constructs. Even when dealing with divine figures like Krishna or Chanakya, he refrains from deifying them in the traditional sense. Instead, he focuses on their intellectual prowess, leadership, and human vulnerabilities. His characters, whether historical or mythological, are rendered as real and believable within the context of their times. They make strategic decisions, face moral dilemmas, and occasionally embrace ambiguity. This nuanced portrayal reflects Sanghi’s emphasis on context over caricature and history over hagiography. His novels thus operate at the intersection of storytelling and historiographical inquiry, offering readers not only entertainment but also a form of informal scholarship.

Another distinctive feature of Sanghi’s novels is their interdisciplinary reach. He draws from an impressive array of sources—ancient scriptures, archaeological reports, linguistic theories, cosmology, and political science—to weave his intricate plots. This breadth of engagement gives his work an intellectual gravity that distinguishes it from other popular mythological fiction. Where Neelakantan might focus on revisiting a character’s untold story, and Tripathi might focus on exploring dharma through metaphysical allegories, Sanghi attempts to present mythology and history as a connected and evolving matrix of ideas, ideologies, and institutions. His works appeal to readers who appreciate layers, contradictions, and the thrill of connecting scattered dots across time and space.

Furthermore, Sanghi’s novels often carry a subtle critique of contemporary Indian society. Chanakya’s Chant, for instance, critiques the nature of modern Indian politics while simultaneously invoking the timeless strategic brilliance of its ancient counterpart. This dual critique makes the novel both historically reflective and politically resonant. Sanghi’s engagement with contemporary themes—corruption, communalism, media manipulation, and the erosion of ethical leadership—is subtle but effective, lending his narratives a sociopolitical depth. He does not shy away from controversial ideas, nor does he resort to sensationalism. Instead, he invites the reader to reconsider the past not as a nostalgic utopia but as a lens through which to understand the present.

In terms of structure, Sanghi often adopts a dual-timeline format, alternating between ancient and modern narratives. This not only enhances the suspense but also reinforces his central argument that the past and the present are inextricably linked. His transitions are smooth, his character arcs well-crafted, and his endings often leave the reader contemplating broader questions about civilisation, legacy, and human ambition. This narrative complexity is rarely attempted in Indian popular fiction, which often favours linear plots and character-driven storytelling. Sanghi’s architectural narrative design—complete with intertextual references, footnotes, and sometimes even bibliographies—demands an intellectually engaged reader and rewards them generously.

It is also worth noting that Sanghi, unlike many of his contemporaries, is remarkably open about his sources and influences. His authorial transparency adds to the credibility of his work. He does not claim to have discovered eternal truths but instead invites the reader to question, explore, and arrive at their conclusions. This epistemic humility—rare in the often dogmatic world of mythological fiction—makes his writing both provocative and participatory. Readers are not passive recipients but active collaborators in the intellectual journey.

Stylistically, Sanghi eschews florid prose in favour of clarity and control. His language is not ornamental but functional, facilitating the transmission of complex ideas without unnecessary embellishment. This stylistic choice mirrors his thematic intent—to educate while entertaining. While Tripathi and Neelakantan rely on dramatic intensity and emotional resonance, Sanghi’s appeal lies in his logical precision and conceptual layering. His novels are essentially knowledge-thrillers, where the excitement arises not from action alone but from intellectual discovery.

In conclusion, what sets Ashwin Sanghi apart is his ability to blend narrative agility with scholarly depth. His novels are not mere stories; they are intellectual excavations that unearth the philosophical, political, and scientific undercurrents of Indian civilisation. In a genre that is often saturated with simplistic retellings and formulaic plots, Sanghi dares to challenge the reader’s intellect, broaden their historical consciousness, and provoke deeper reflection. While authors like Amish Tripathi and Anand Neelakantan have significantly enriched Indian mythological fiction through their emotionally charged and empathetic narratives, Sanghi offers something different. This cerebral odyssey connects the ancient and the modern, the sacred and the profane, the mythical and the real. In doing so, he not only redefines the contours of Indian popular fiction but also asserts the enduring relevance of India’s cultural and intellectual legacy.

Ashish for Featured Books